In economic theory, a “public good” is non-excludable (access cannot be denied) and non-rivalrous (one person’s use doesn’t diminish another’s). Historically, this meant clean air, national defense, and critical infrastructure.

As conversations intensify around the India AI Impact Summit this February, we confront a more fundamental question: Can the world’s two largest democracies establish AI itself as the defining public good of the 21st century, and in doing so, chart a democratic alternative to authoritarian models of technological governance?

The Summit’s mantra: Sarvajana Hitaya, Sarvajana Sukhaya (Welfare for All, Happiness for All), captures something essential. But mantras alone accomplish nothing. The gap between principles and practice is where most AI initiatives fail. The question is whether we’re willing to do the hard work of translating vision into deployed systems that genuinely serve people at scale.

India as Laboratory, Not Follower

Here’s what most Western AI discourse misses: India isn’t positioned as a follower adopting models designed elsewhere. At 1.4 billion people, India is the essential laboratory for inclusive AI that can work for the next six billion people globally.

At that scale, inclusivity isn’t a moral add-on, it’s the entire technical requirement. You cannot serve 1.4 billion people with solutions designed for the already-connected few. India’s constraints like linguistic diversity, infrastructure variability, economic stratification, intermittent connectivity are not problems to be overcome. They are the design specifications for AI systems that will actually work for most of humanity.

When Gaurav Agarwal helped orchestrate the rollout of 4G infrastructure across India, creating the largest connected population on Earth, that was strategic preparation for the AI era, proving that massive-scale connectivity could be achieved in resource-constrained environments. The IndiaAI Mission’s commitment to democratizing compute access at under $1/hour continues this trajectory of making AI capabilities a utility, not a luxury.

Bottom-Up Architecture: Building From Constraints

The most critical design principle for AI as a public good: you cannot scale down from enterprise solutions. You must architect from the bottom up, starting with the constraints of the least-connected users.

An AI diagnostic system designed for a well-equipped hospital will fail in a rural clinic. But the system that works in the village clinic, operating on the edge, with intermittent data, designed for basic health workers, can be enhanced for any hospital. The reverse is not true.

Precision farming tools designed for large operations assume reliable connectivity and expensive equipment. Tools designed for smallholder farmers which can operate offline, on basic smartphones can scale anywhere. Credit scoring systems trained on traditional banking data exclude billions, while systems using alternative data expand access without sacrificing risk management.

India’s constraints force the development of AI systems that are resilient, resource-efficient, and genuinely inclusive. These become global standards, not regional adaptations.

Citizen Agency: Empowered Actors, Not Passive Recipients

Beyond the Master Orchestrator paradigm of humans orchestrating AI capabilities, lies a stronger principle: citizens themselves must be empowered actors in how AI affects their lives, not passive recipients of decisions made elsewhere.

This requires participatory design where affected communities shape development, transparent operation where citizens understand how decisions are made, meaningful recourse when systems err, and the capacity to participate in decisions about which AI systems get deployed for what purposes.

For authoritarian models, citizen agency is a constraint to be minimized. For democratic AI, it’s a design requirement to be maximized.

Four Strategic Sectors

- Healthcare: Joint US-India development of diagnostic systems leveraging American architectural expertise and India’s diverse datasets can create tools that work in village clinics with intermittent connectivity, positioning both nations as leaders in health security.

- Agriculture: AI-powered precision farming combining U.S. satellite technology and Indian agricultural data addresses food security, but these systems must be designed from the farmer’s constraints upward, not enterprise systems stripped down.

- Education: Multilingual AI platforms that adapt to local dialects build cognitive infrastructure for democratic participation. India’s linguistic diversity makes it the ideal testing ground for truly multilingual systems.

- Financial Inclusion: AI-driven credit scoring using alternative data can expand access to formal economic systems, demonstrating that democratic frameworks deliver tangible prosperity to populations often left behind.

Watchful Optimism and the Implementation Gap

The path forward requires extreme optimism, but watchful optimism with eyes wide open to risks. We must believe AI can genuinely serve as a public good while remaining vigilant about bias, privacy violations, and power concentration. Neither naïve techno-utopianism nor regulatory paralysis serves the public interest.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: most AI initiatives die in the implementation gap, which is the space between strategic vision and ground-level deployment. Summits and frameworks matter, but they are the beginning of the conversation, not the endpoint. The real measure is systems deployed and operating in village clinics, on farms, in classrooms.

This requires sustained commitment over years, operational excellence in the unglamorous work of training and maintenance, rigorous measurement of outcomes that matter (lives improved, income increased, education accessed) and cross-border learning so success in one context becomes shared knowledge.

The Strategic Stakes

Some nation’s centralized, state-controlled AI model represents one possible future. The US-India partnership must demonstrate a superior alternative: distributed, democratically accountable, optimized for human flourishing. Not just morally superior, but demonstrably more effective at delivering prosperity and opportunity to diverse populations.

The nations that successfully deploy AI as genuine public infrastructure will shape global norms, attract talent and investment, and lead in the 21st century’s defining sector. India’s unique position as a laboratory for inclusive AI at scale creates an opportunity for both nations to lead globally.

The technology is ready. The strategic logic is clear. What remains is the hard work: building consensus across stakeholders, architecting systems from the bottom up, preserving citizen agency, measuring outcomes rigorously, and sustaining commitment through messy implementation.

If the U.S. and India can demonstrate that democracies excel at deploying transformative technology for public benefit, we will have secured democratic leadership in the age of AI.

The conversations happening now set direction. But the real work, and the real opportunity, lies in the years of implementation ahead. The question is whether we have the courage for watchful optimism and the commitment to turn principles into practice.

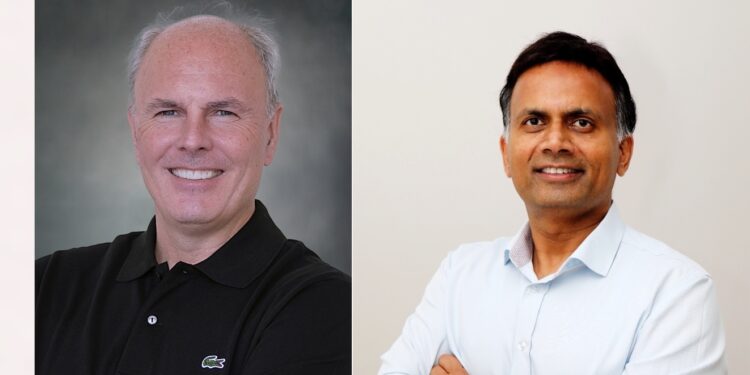

About the Authors

Cathal McCarthy is Chief Strategy Officer at Kore.ai. He previously spent 16 years at Apple during its transformation into the world’s most valuable company.

Gaurav Agarwal led the rollout of 4G infrastructure across India, creating the digital foundation for the world’s largest connected population. He previously worked at Apple, where he contributed to global technology scaling initiatives.

Also Read: How CIOs and CISOs Can Govern AI Without Slowing the Business