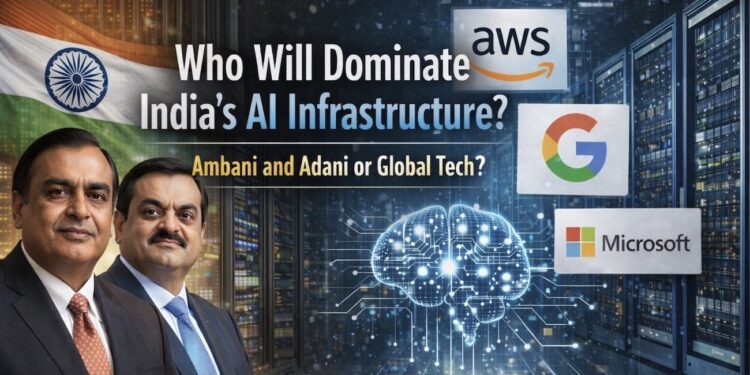

The past two days have crystallized what industry watchers suspected for months: a race for India’s AI infrastructure is underway, and it is multi-fronted. Two Indian conglomerates have laid down very large, public financial markers for on-shore AI capacity; at the same time, global cloud providers continue to announce multi-billion-dollar investments and regional expansions. The practical question for enterprises, regulators and investors is not whether one side will try to dominate, but whether any single player can convert announcements into sustained market share, given technical, commercial and regulatory frictions.

- Reliance Industries’s parent group publicly committed roughly $110 billion for AI and related data-centre investment.

- Adani Group announced a $100 billion programme to build renewable-powered, AI-ready data-centre capacity by 2035.

- Major global clouds are not standing still: public plans and reported commitments by firms such as Amazon Web Services, Microsoft and Google add tens of billions in separate regional investments and capacity expansion over the coming years.

What do these numbers mean?

These investment commitments matter; they set narratives, influence supply-chain signings and open doors for policy support and partner commitments. But capital commitments are not the same as immediately deployable AI capacity. The transformation from commitment to racks, GPUs, reliable power and fibre takes years and depends on several binding constraints: grid stability and large-scale renewable supply, land and permitting, secure subsea and terrestrial network connectivity, talent to design and operate AI-scale clusters, and the global supply of accelerator chips and networking silicon.

Scale comparison

India’s Reliance’s $110 billion and Adani’s $100 billion place domestic players in the same discourse as global cloud investments measured in the tens of billions per vendor for a single country, but there are two important caveats.

First, these conglomerate totals are often multi-year, multiproject spends that can include related ecosystem bets (telecom buildouts, green energy, software stacks, and adjacent manufacturing) rather than only turnkey data-centre construction.

Second, hyperscalers’ investments (for example, AWS’s and Google’s multi-billion regional investments, and Microsoft’s public multi-billion pledges) are concentrated on cloud region builds that pack software, managed services and a global operational footprint, the kind of end-to-end platform many enterprise customers buy. The result is overlapping but not identical value propositions.

Domestic advantage: where Ambani and Adani are credibly strong

- Site economics and energy integration. India’s Ambani and Adani own or control large energy-generation portfolios and logistics footprints that reduce the unit cost of running energy-hungry AI clusters when compared to third-party land leasing and grid purchases. That matters for operating margins at multi-GW scale.

- Regulatory and sovereign posture. India’s policy conversation now explicitly privileges data localisation and sovereign AI initiatives; domestic champions are naturally better positioned to capture government and regulated workloads that require on-shore custody.

- Integrated industrial play. Conglomerates can internalise parts of the supply chain, energy, ports, real estate, allowing them to underwrite long-lead infrastructure projects and attract anchor industrial customers.

Global Tech’s enduring advantages

- Stack depth. Hyperscalers bring mature cloud platforms, developer ecosystems, global ML tooling, and a catalogue of managed AI services. For many customers, the incremental cost of running on a global cloud is outweighed by the time-to-market and software productivity benefits.

- Customer trust and multi-region resilience. Global firms offer tested, compliant stacks for multinational customers and disaster-recovery architectures that are hard to replicate immediately for a domestic data centre operator.

- Model & IP ownership. Many leading pretrained models and managed AI services originate from these global firms or their partners; hosting capacity alone does not substitute for proprietary model IP and managed AI ops.

Who will capture which share?

Expect an oligopolistic, multi-stakeholder market rather than a single dominator. Practical segmentation is likely to emerge along use cases:

- Sovereign/regulatory-sensitive workloads (government, defence, critical infrastructure): tilt strongly to domestic campuses operated by conglomerates and trusted local providers. Ambani/Adani have the narrative, capital and energy economics to outcompete here.

- Enterprise cloud-native and global SaaS workloads: will continue to favor hyperscalers because of platform breadth and global reach. Large Indian enterprises with global operations will likely run hybrid architectures.

- AI-native, high-compute inference and training for local language and application models: a mixed result. Local campuses can host inference/specialised workloads close to data; hyperscalers will host large-scale training and cross-border services unless strong policy barriers push that work on-shore.

Execution risks and constraints that blunt headline dominance

- Chip and accelerator supply. GPUs and AI accelerators are globally constrained; building data halls without a secured, long-term chip supply leaves capacity idle or underperforming.

- Operational experience. Operating hyperscale AI workloads is a specialist discipline, with power distribution, rack cooling, cluster orchestration, ML ops, with decades of learning baked into cloud operators. Conglomerates will need to recruit or partner to close that gap.

- Customer economics and multi-cloud preference. Many large customers are explicitly avoiding vendor lock-in; they will demand interoperability and hybrid options, forcing domestic campuses to offer easy on-ramps to global clouds or to accept a segment-limited role.

- Monetization uncertainty. Converting capacity into recurring, high-margin services requires robust sales pipelines and ecosystems of ISVs and integrators.

Signalling and early commercial moves

Two recent developments are useful signposts. First, global tech continues to sign multi-billion-dollar commitments in India; these are not symbolic; they are commercial bets on a long tail of enterprise demand. Second, domestic and local partnerships (for example, reported agreements between Indian data-centre businesses and advanced AI customers) show the market is already converging on hybrid, partner-driven supply models rather than exclusive vendor monopolies.

Bottom line, a calibrated verdict

Ambani and Adani are credible contenders to own large swathes of India’s physical AI infrastructure thanks to capital, land and energy economics. That does not equate to absolute market dominance. Global Tech retain decisive advantages in software, models, and global enterprise relationships. The most probable market structure is a layered oligopoly: domestic giants controlling on-shore sovereign campuses and significant capacity, coexisting with and partnering with global cloud providers that deliver the platform, models and cross-border services most enterprises demand.